In 1920, in a baseball game with the New York Yankees, Cleveland Indians batter Ray Chapman was hit in the head by a pitched ball. Witnesses said Chapman apparently lost sight of the ball, because he made no attempt to move or duck.

Hours later, he died. Chapman is the only major league player ever killed in this manner.

The condition of the ball was considered a factor in Chapman’s death. In those days, pitchers were expected to “break in” new baseballs, which are glossy and slick and hard to grip. Pitchers rubbed the baseballs with anything handy — dirt, mud, spit, tobacco juice, shoe polish. They nicked the leather with blades and roughed it up with sandpaper.

As a result, game balls varied widely in condition. They could be damp. They could wobble in flight. Worse, they tended to be dark and mottled in color, making them harder to see.

After the Chapman incident, Major League Baseball was motivated anew to find a way to season new baseballs without the negative side effects. Nothing surfaced.

Finally, in the late 1930s, a third-base coach for the Philadelphia Athletics, Lena Blackburne, found a solution that wasn’t quite magic, but came close. His method is still used today by every MLB team and most minor league and college teams.

Blackburne grew up in Palmyra, New Jersey, a small town on the Delaware River just north of Philadelphia. He knew from his childhood that the river mud near Palmyra is unique. It has an unusually smooth, creamy, clay-like consistency and holds minimal moisture. He decided to try the mud on a baseball.

Blackburne found that a tiny amount of the river mud — one finger dipped in the stuff — was enough to spread over a baseball and work the magic. The mud seasoned the leather, eliminated the gloss, and slightly roughened the surface, all without discoloring the ball. Baseballs looked the same before and after treatment.

Blackburne’s rubbing mud was an instant hit with the Athletics. Word soon spread around the league, and other teams began asking Blackburne for a supply of the river mud.

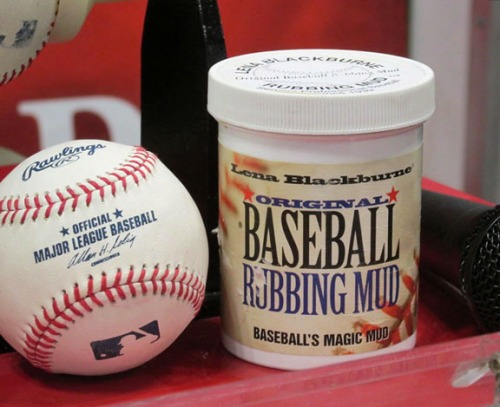

At that point, Blackburne officially went into the business of selling Lena Blackburne’s Baseball Rubbing Mud — Baseball’s Magic Mud.

Experts say the mud gets its characteristics from the type and amount of clay in the soil and the chemistry of the river. The Delaware is a “blackwater” river, rich in iron oxide, and it flows through highly acidic soil.

It’s also a fact that mud from anywhere along the river won’t do. Blackburne found that only along about a one-mile stretch of the river do ideal conditions for the rubbing mud exist.

Blackburne kept the location secret. He confided only in his friend John Haas, who became his partner in the business.

The process Blackburne and Haas developed was to collect the mud in buckets, run it through a strainer to remove leaves and other debris, add water, and let it sit in large cans.

Periodically over about six weeks, excess water was drained, and the mud was strained several more times. When no water remained and the mud was perfectly smooth — reduced to the consistency of cold cream or pudding — it was ready to be packaged.

Blackburne and Haas prepared the mud over the fall and winter and were ready to supply the teams the following spring. By the 1950s, every team in baseball was rubbing the magic mud on every baseball.

The mud was a big deal for baseball, but certainly not a money-maker for Blackburne. The market is limited, and a couple of containers will last a team all season. Blackburne’s enterprise was a service to the game and a labor of love.

(Each team needs about two one-pint containers of the mud per year. In 1981, a container sold for $20. The price today is $100. The mud business currently nets about $15,000 to $20,000 per year.)

Blackburne died in 1968 and left the company to Haas. Haas continued the business, still keeping the location secret. When he retired, his son-in-law, Burns Bintliff, took over.

Like Blackburne and Haas, Bintliff ran the mud business in his spare time, holding a job elsewhere to pay the bills. Eventually, he passed the business along to his son Jim, who runs the company today.

Jim Bintliff and his wife Joanne both worked for a small printing company and ran the mud business on the side. Joanne said they were married five years and had two children before Jim finally revealed to her the secret location where the mud is collected.

Eventually, their youngest daughter Rachel is expected to take over the business — if demand for the mud continues.

In 2016, MLB asked the equipment manufacturer Rawlings to develop a ball that didn’t need rubbing mud — a ball that is broken-in and ready to use upon delivery. The rubbing mud, they said, is a hassle for equipment managers, and Mother Nature could decide to stop making it available.

Rawlings continues trying to create a pre-seasoned baseball, but so far has struck out. Pitchers are accustomed to the feel of Lena Blackburne‘s Magic Mud, and the chemists and engineers at Rawlings haven’t been able to replicate that feel to the players’ satisfaction.

“Mud is mud,” said Mike Thompson, Chief Marketing Officer at Rawlings. “But, obviously, mud isn’t mud.”

Meanwhile, Jim Bintliff has been working on another angle for the business. The mud, it seems, works just as well on a football. Many NFL teams now place regular orders.

Jim Bintliff at work.

Leave a comment